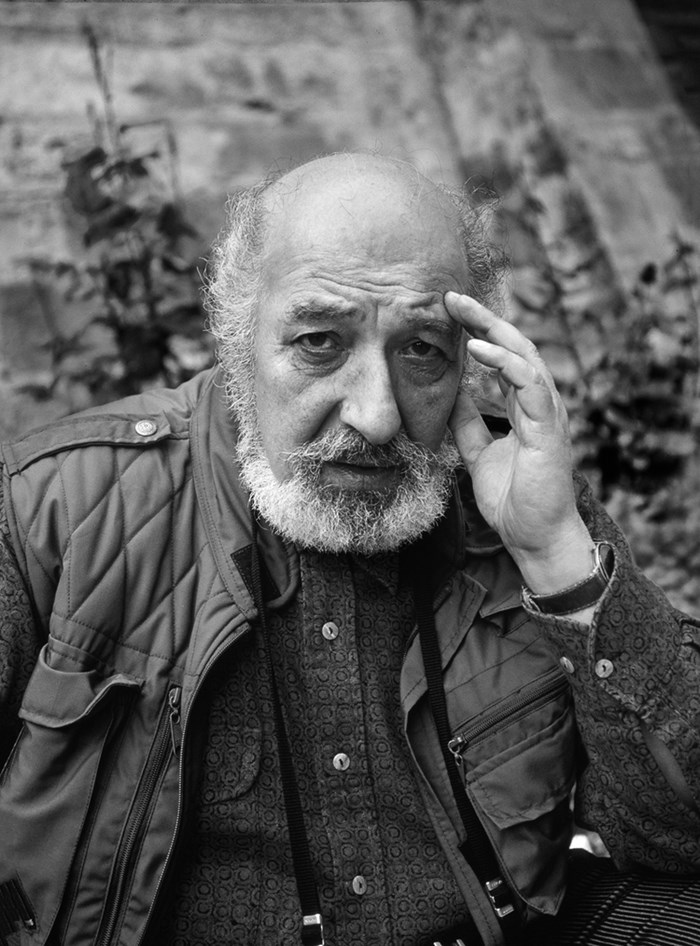

Ara Tatchati Güler (Terteryan)

born 1928

1950 - 1980s

When he was taken into intensive care in 2014, news that the world-renowned photographer Ara Güler had passed away spread instantaneously. Not long after, Güler posted a photograph on Instagram from his hospital bed that showed him giving the middle finger to these rumours. This was a man who had little patience for nonsense and his photography reflected the firm belief in telling the truth as directly as possible. Yet, after kidney failure finally took his life this Wednesday, Güler left behind him a vast photographic legacy of over 800 000 negatives that is anything but straightforward and full of complications which will keep scholars of his work occupied for many decades to come.

The photographer’s much-talked about personal life and career is extraordinary by any given measure. His fame was due as much to his widely publicised photographs as from his idiosyncratic (not to say exotic) status as a non-Western media personality with a global outreach. Born in 1928 to Armenian parents in Istanbul, Güler was exposed to the city’s artistic community from an early age. While attending the Gentronagan Armenian school as a teenager, he also took classes in theatre - a lifelong passion that directly influenced his later photographic work. After a brief stint in Istanbul’s film studios, he turned to journalism, taking a job at Yeni Istanbul newspaper in 1950 that eventually led him to take up the photo-camera. Armed with an innate talent for capturing dramatic details and evoking atmosphere, Güler was soon running the photo department of the popular illustrated magazine Hayat and corresponding with all the major press outlets in Turkey. At the age of only thirty, the photographer was receiving commissions from prestigious international media corporations such as Time-Life, Paris Match, Stern and the British Sunday Times. These assignments caught the attention of Henri Cartier-Bresson who invited Güler to join Magnum photo agency in 1961 – a watershed moment that would ensure the photographer’s rapid rise to international fame.

The 1960s was a particularly opportune decade for an ambitious photographer from the ‘East’. Turkey was emerging as a favourite hot-spot for the Euro-American jet-set and Güler was on hand to photograph almost every major celebrity that set foot on the Bosporus. He also travelled widely, making special photo-reportages on Winston Churchill, Indira Gandhi, Bertrand Russel, Maria Callas, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali and many other key figures in global politics and the arts. Over the years, this glittering gallery of luminaries expanded to such an extent that it could rival the work of that other Armenian photo overlord, Yusuf Karsh, whose highly polished, ‘sculptural’ approach to portraiture was in stark contrast to Güler’s edgy, off-the cuff style of photography.

What eventually consolidated Güler’s name as a major name in twentieth-century photography, however, was his extensive and much more personal series on Istanbul’s rapidly transforming urban environment and the communities living in Turkey’s remote provinces. Saturated with achingly heartfelt poetry, his smoggy pictures of Istanbul’s ancient vistas, streets, harbors, crumbling suburbs and their vibrant inhabitants appear like a hazy black and white dream. Began at a time when Turkey was entering an unprecedented stage of industrialization in the early 1950s, these visual narratives are stamped with the melancholic realization of fatal disappearance. Like Eugène Atget before him, Güler consciously turned into a chronicler of reality that was irretrievably receding into the past, leaving behind a shadowy trace that would only survive as an imprint on his high-contrast, grainy photographs. The tender nostalgia that permeates these series is a complicated beast. In many interviews Güler has often expressed a sense of mourning for the ‘old’ Istanbul with its rich multicultural population, historically layered architecture and views, claiming that his photographs are unmitigated ‘visual histories’ of that which has been. This memento-mori aspect is one of the primary reasons for his work’s iconicity, which has been compounded by countless exhibitions, albums, postcards and reverential essays by the likes of Nobel-prize winning author Orhan Pamuk.

Yet, photography scholars such as İpek Türeli have argued that Güler’s photography is as much responsible for constructing historical memory as it is in recording the passage of time. Indeed, the elegiac tone of Güler’s photo-albums like the 2008 A Photographical Sketch on Lost Istanbul presents us with a vision of the past as a distilled and idealised antithesis to the hubris of our times. Such idealisation, of course, has no basis in historical reality but may in actual fact stem from a deep and perhaps unacknowledged trauma that inevitably laced the Turkish-Armenian identity post 1915 Genocide. Forthrightly proud of his Turkish citizenship, Güler was always reticent when it came to enquiries about his Armenian heritage. He often defined himself as an ‘Istanbulite’ – a son of a great city rather than a nation. And yet, digging deeper into the lesser-seen recesses of his enormous photographic archive reveal a constant, albeit very discreet compulsion to document whatever remained of the Armenian presence in Turkey. Disguised under the generic rubrics such as ‘Lost Istanbul’ or ‘Monuments of Anatolia’ are extensive groups of photographs depicting the remnants of Ottoman Empire’s Armenian communities and their architectural masterworks scattered around Eastern Anatolia. Made between 1950s and 1980s, these rather ambivalent images speak of loss and absence, a painful inner rupture that galvanised Güler’s compassionate and equally wounded perspective on his homeland and the world at large.

Towards the end of the photographer’s life, these supressed sentiments became even more pronounced. When he visited Armenia in 2013 on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Armenia, Güler donated over 130 prints to the museum and allegedly considered moving his entire archive to Yerevan on the condition that it would be housed in a museum dedicated to his oeuvre. In the end the archive was acquired by the one of the largest Turkish corporations, the pro-government Doğuş Group, which inaugurated the Güler museum just months before the photographer’s death. It will undoubtedly join the Ara Café in Beyoglu as one of Istanbul’s prime attractions and an iconic monument to a man who so successfully broke through political and cultural barriers to create one of the most evocative and moving photographic chronicles of the twentieth-century. This dedication to capturing a sense of time and place may seem today as charmingly innocent and distant but is also precisely why Güler’s work demands revaluation and continued attention today. His unbridled focus on togetherness, creativity and the sheer pleasure of living crystallises values that are shared by all communities and are under threat in a world that increasingly alienates us from work, place and each other. To delve into the emphatic realm created by Güler’s gaze on humanity is to discover the mutuality that overrides conflicts by using photography as a powerful bridge towards forgiveness and understanding. It is an achievement worthy of any great artist – a label which Güler humbly repudiated throughout his life.

Nationality

Turkish, Armenian

Region

Turkey

City

Istanbul

Activity

artistic, documentary, photo correspondent

Media

analogue photography

Bibliography

Kochar, Vahan. Hay lusankarichner (in Armenian), self-published, 2007, p 130-142

Güler, Ara. Istanbul, Ilke Basin Yayin, Istanbul, 2012

Güler, Ara; Pamuk, Orhan. Ara Guler's Istanbul: 40 Years of Photographs, Thames & Hudson, London, 2009

Güler, Ara. A Photographical Sketch on Lost Istanbul, Dunya Sirketler Brubu, Istanbul, 1994