Kevork Abdullah (Abdullhanyan)

1839 - 1918

1850 - 1890s

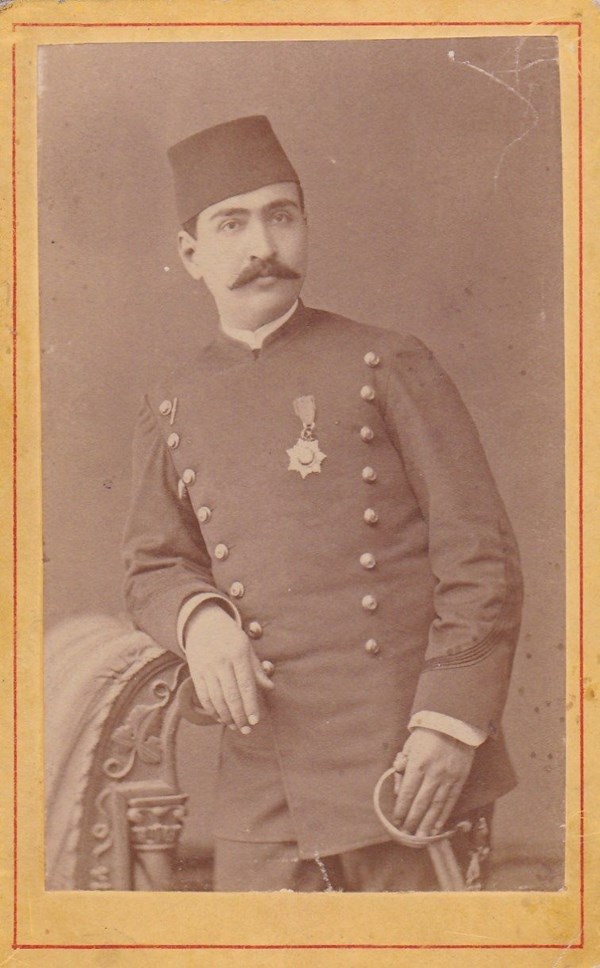

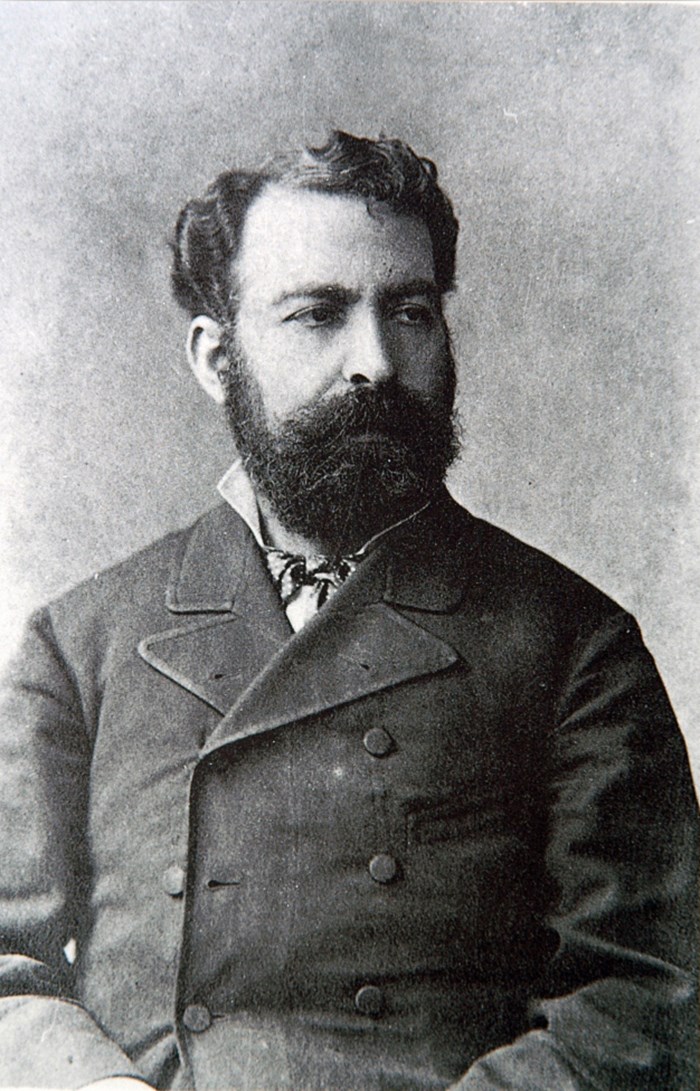

Junior Representative of the Abdullah Family Brotherhood, Kevor Abdullah was one of the most prominent and active cultural figures of the Constantinople in the second half of the 19th century. He was born in the Armenian-Catholic family of silkworm Abraham Abrahamian (Astvatsaturyan). Armenian-populated neighborhood of Constantinople. During his studies at Mkrtich Peshiktashlyan, at the Enlightenment College, Gevorg was deeply rooted in patriotism, which grew deeper in 1852 when he moved to Venice to study at the Murad Rafaelian College. His teacher here was Ghevond Alishan, who later would greatly support the formation of the Abdullah Gul's photo career. (1)

Despite his hopes of pursuing his studies in Europe, Kevork has to return to the end of 1857 due to family reasons. Constantinople Here his older brother, Vichen, acquired a photographic workshop by a German chemist named Rafach, specializing in the preparation of daguerotypes. Together with his elder brother Joseph, Gevorg is involved in this new family business, thus becoming one of the co-founder of the first local photography photography in the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the 1850s, the daguergot was a remedy. Understanding their lack of experience as well as the need to get acquainted with new photography technologies, Vichen and Kevork are soon to leave for Venice, St. Petersburg. Lazarus then Paris. Through Ghevond Alishan's efforts, they succeed in drawing close to photographer Baron Taylor and Koms Aguado who introduce the novelty of Armenian photographer to the innovations of that technology and help them to establish contacts with Paris as well as K. Aguado. With various individuals who are important in political and cultural life in Constantinople.

Thanks to Count Aguado, the brothers are given the opportunity to approach the French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Marcos de Moustiey, whose ties with the Ottoman High Dormitory will soon give the Abdullah Brothers a chance to appear in Sultan Abdülaziz. In 1863, Abdulaziz instructed photographers to make a photo portrait of political and economic reform and modernization. Presenting the most advantageous to the unlucky ruler, the portraits of the Abdullais deserve the approval of Abdulaziz and immediately spread as his official photographic image in the Ottoman Empire and beyond. For this service, the Abdullahs are also awarded the title of Emperor's Photographers and the right to use the Sultan's Sign, which, according to photographer historian Bahatin Oztuncha, was "a miraculous key that could open any door."(2)

The other great achievements of the Abdullaids are followed by the great success. In 1867, they came across Istanbul's wide-ranging panoramas and photos of ethnographic nature at the Paris World Exhibition and captured the attention of French and English press. During that same period, thousands of customers have appeared among prominent figures such as Austrian Empress Juchen, Mark Twain, K. Almost all Ambassadors of the European states of Constantinople, Hovhannes Aivazovsky and others. The photographer's studio in Pera district becomes one of the important conventions of the Armenian community of Constantinople. Here were great Armenian writers, artists, musicians and politicians who were discussing ways to improve the Turkish-Armenian situation and undertook new cultural projects. In the early 1870's, Gevorg was more active in patriotic activities. He continues to collaborate with Ghevond Alishan who regularly receives photocopies of medieval Armenian art from Gevorg. In 1872, Gevorg translated from German and publishes his own works by Orientalist Andreas Mordman's "Armenian Separators", one of the pivotal studies of the Urartian language. This patriotic and nationalistic inclination of Gevorgyan was especially significant after Sultan Abdulhamid's assassination. Besides Ghevond Alishan, he had close friendships, business and correspondence with prominent figures such as Srbouhi Tusab, Minas Cheraz, Grigor Balyan, Grigor Zohrab and Tigran Chukhajyan.

In 1875 under certain pressure, Kevork and his brothers refused Catholicism by accepting the Church of the Armenian Apostolic Church. A few years later, after the end of the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-78, Gevorg organized a lavish reception for the commanders of the victorious Russian army. According to some sources, he is proudly expressing his desire to see Western Armenia as independent of the Ottoman Empire.(3) The news is passed to the Sultan who immediately deprives the Brothers of the Imperial Photographer's title. It was an irreversible blow to the photographer. Losing large and profitable state orders, as well as the support of the Ottoman elite, the Abdullayan pavilion is experiencing a financial decline. Perhaps trying to soften the situation, Gevorg, along with his brother Joseph, moved to Cairo in 1886, where he was officially invited by Khaled, Tepik Pasha, to Egypt. This branch of photography Cairo is functioning until 1896 when Gevorg decides to return to his native city.

Abdullah Frères was a big business venture where there were many assistants and employers besides three brothers. As a rule, they were representatives of the families of Joseph and Vicen (Kevork remained a bachelor and had no offspring), or young people from other Armenian families. That is why it is now impossible to determine who is responsible for making, processing, printing, and recording albums. Most likely, this was the result of a joint work, and the question of personal authority was not there.

Nevertheless, it is possible to separate the works of Kevork Abdullah from the Egyptian region as a personal work of this photographer. In 1887, Joseph, accompanying Gevorg, did not stand up to the climatic conditions and returned to Istanbul. He was replaced by his son, Abraham, who has mostly responsible for administrative and technical work, leaving a more responsible job of photographing his cousin.

In the mid-1880's, the photography style and genre preferences of the studio had long been established. Apart from individual and group portraits, they included urban landscapes, genre scenes, images of ethnographic "species", documentaries of traditional holidays and parades, and photographs of historic-architectural monuments. Though all of these genres exist in the Egyptian photographs of Gevorg, more attention was given to the capture of monuments and "indigenous" nations. Unlike Istanbul's similar photographs, George's photographs were made in a more dynamic, instant style. While photographing historic and modern architectural constructions in Cairo and the surrounding area, he did not try to isolate them from the surrounding life, creating nostalgic images of the East in time. Cairo's photos show a rapidly changing, up-to-date city, its diverse, multicultural inhabitants. While painting ethnographic "typepieces of natives," Gevorg was often trying to convey the full psychological character of the individual, which did not allow the observer to easily define these characters.

In Cairo, there is still a certain direction for documenting and "maintaining" the past through photography. The ancient photographer, like many European tourists, was saddened by the Egyptian passage from medieval to modernity, as a result of which not only the local lifestyle and culture but also many significant monuments were destroyed. The "conservative" melancholic aspiration is expressed especially in George's interiors photographs where the Arab residents, who are occupied with loungent traditional dresses, are shocked by the mood of the scene.

Generally, all photographic products of Kevork's Egyptian, as well as the Istanbul Brother's photographic photographer, are characterized not only by the creation of the Middle Eastern local photography, but also the transition from the "universalist" photography to the modernist nationalism's culture. Although Vicen Abdullah was able to restore Abdulhamid's trust and receive the title of an imperial photographer in 1888, Kevork, how can he judge the photographer's memories, mostly did not engage in photography after returning to Istanbul, preferring to leave the photography job younger members of his family? In 1899, the entire archive of the pavilion's black photographs was sold to the constant opponent of Abdullah Frères, to Saba and Joale's studio, which later reprinted the images of the Abdullayans. Gevorg spent the last years of his life in London, where he studied literature and wrote his memoirs, which later became the basis of Esiya Tayitsi's biography in 1929. first monograph in Armenian language dedicated to photographer's work.

1) The biographical data of the photographer are mainly extracted from the Essay Taisheti Memorandum Toast and former Emperor's Photographer Kevork Abulullah, St. Lazarus, Venice, 1929

2) See Bahattin Öztuncay, The Photographers of Constantinople, vol.1, Aygaz, Istanbul, 2003, p. 185

3) In the same place, p. 220

Nationality

Armenian, Ottoman

Region

Egypt, Ottoman Empire

City

Constantinople, Cairo, London

Studio

Abdullah Frères

Activity

studio, documentary

Media

analogue photography

Bibliography

Tayetsi, Yessai. Hushagir Kenats ev Gortsuneutyan Nakhkin Kayserakan Lusankarich Gevorg Abdullahi [in Armenian], St. Lazarus, Venice, 1929.

Öztuncay, Bahattin. The Photographers of Constantinople, vol.1, Aygaz, Istanbul, 2003

Pinguet, Catherine. Istanbul, Photographes et Sultans, 1840-1900, CNRS, Paris, 2011

Collections

Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Lusadaran Armenian Photography Foundation, Yerevan